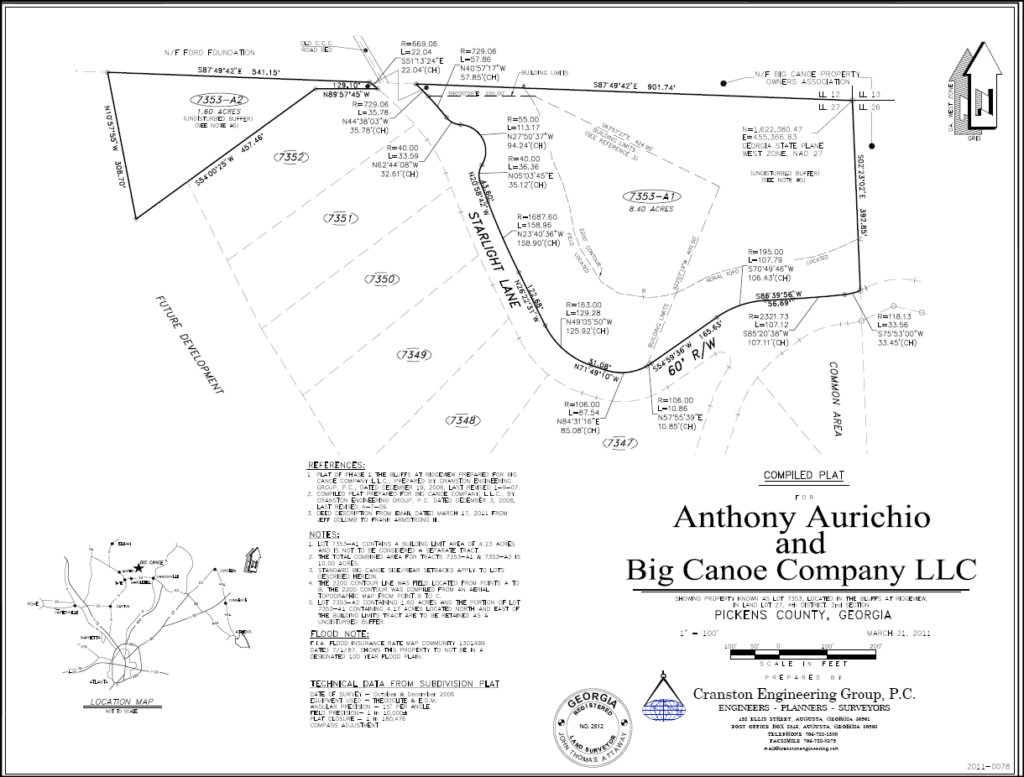

This blog concerns subdivision plats. During the development of a subdivision, the developer submits a subdivision plat to the county for approval. Once approved, the developer records the subdivision plat on the county’s real estate records.

Alleys, Parks and Water Courses, Drains, Easements and Public Places

The subdivision plat includes not only the dimensions of the developed lots but also includes alleys, parks and water courses, drains, easements, and public places. As the developer sells the lots in the subdivision, the deeds transferring the lots to the new owners mention the subdivision plat. When the deeds reference the plat, the new owner gets an automatic easement to use the alleys, parks and water courses, drains, easements and public places marked on the subdivision plat.

Transfer of Public Space from Developer to the HOA

Once the developer finishes the subdivision, the developer usually transfers the alleys, parks and water courses, drains, easements and public places to the neighborhood’s homeowner’s association.

Dedication to Public by the Developer

Recording a subdivision plat showing areas set apart for public use creates not only a grant of an easement to the purchasers of the property, but also raises a presumption of intent to dedicate to the public. However, to complete a dedication of land to public use, the developer must not only offer to dedicate, but the county must accept the offer.

What Happens When a Public Space Isn’t Used

Sometimes, after the developer transfers the public area shown on the subdivision plat to the HOA, but the area is never used. And often, the HOA fails to pay taxes. When this happens, the county will have a tax sale and sell the property.

As mentioned above, each lot owner obtained a right to use the public area when they purchased their lot. The right to use the public area is considered an express grant and is an unalterable property right. The rationale is that the price of the lots included the use of the public areas. This principle is true even if the lot owners have never used the public space.

Call Us!

If you have questions about a subdivision plat or property rights, call us at 404-382-9994 to speak with an attorney.