Defintion of Negligence

Entire law school classes focus on negligence and its application, so this blog is a very general introduction to one of the negligence-related concepts called negligence per se.

Negligence is the failure to take proper care in doing something. The most common example is an automobile collision. No one intends to cause an automatable collision. But, if a driver isn’t paying attention and rear-ends another vehicle, such lack of care constitutes negligence.

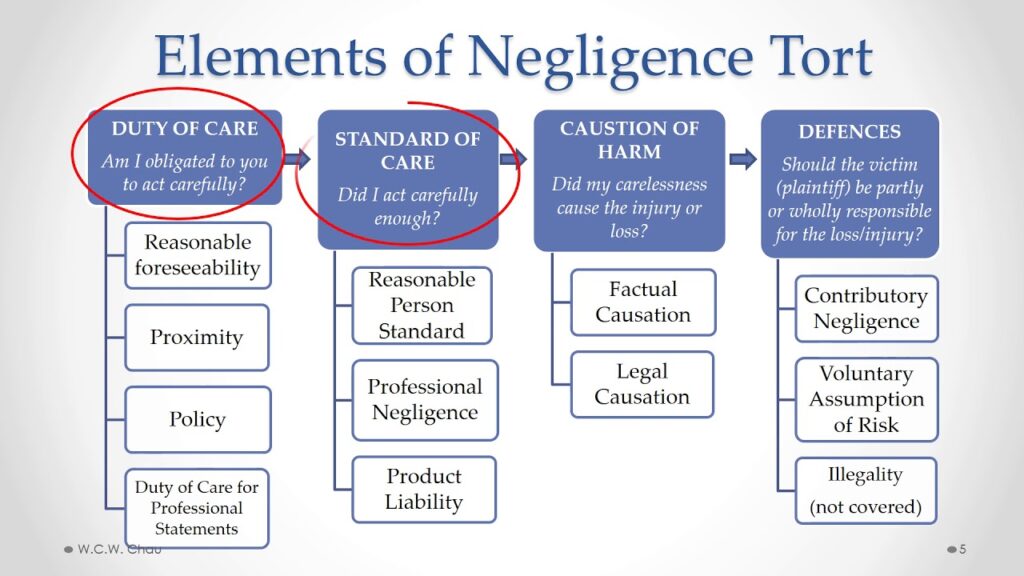

Elements of Negligence

Four elements are required to establish negligence: (1) a legal duty that the defendant owed to the plaintiff, (2) a breach of that duty, (3) an injury, and (4) proof that the negligence caused the injury.

Negligence Per Se and Breach of Duty

So what is negligence per se? Under Georgia law, violating a statute, ordinance, or mandatory regulation may constitute negligence per se. To prove negligence per se, you must show a violation of a statute, that the harm complained of was the harm the statute was meant to protect against, that the person harmed fell into the class of persons the statute was intended to protect, and that the violation caused the injury. Gleaton & Associates, Inc., v. Cornelius, A22A1403 (February 8, 2023).

While not intuitive, negligence per se addresses the first element listed above: the legal duty owed. Lots of times, it isn’t clear whether someone has a duty to another person or what that duty consists of. With negligence per se, if a statute, ordinance, or regulation applies, violation of such a rule will satisfy the obligation to show a breach of a legal duty.

An Example of Negligence Per Se

In Gleaton, the case mentioned above, a tenant alleged the negligent filing of a dispossessory lawsuit against her. OCGA § 44-7-58 states that “[a]nyone who, under oath or affirmation, knowingly and willingly makes a false statement in an affidavit signed pursuant to Code Section 44-7-50 . . . shall be guilty of a misdemeanor.” The tenant alleged the landlord had violated that statute and was liable for negligence. Ultimately the court ruled for the landlord because it ruled the allegations in the dispossessory were not false.

Call Us!

Negligence per se is one of the many nuances in the law that we use to win cases for our clients. If you are injured or wronged by someone else, please call us at 404-382-9994 to discuss your legal options.